(Seoul=Yonhap Infomax) The world is waging a war on debt. Across the globe, citizens have grown reliant on borrowing, living beyond their means—a problem that has evolved from a personal issue into a broader social challenge. Much like a household whose spending outpaces its income, government finances have also seen expenditures surpass revenues. The mounting burden of sovereign debt, accumulated over years, can no longer be ignored. Policymakers are now forced to confront this issue and seek solutions.

The answer: financial repression. This is the strategy by which the US government, facing a record $37 trillion in national debt, seeks to dilute its obligations rather than pay them down directly. This covert approach, now spreading from the US to Japan, marks the dawn of a new era of financial repression.

To address its debt problem, the US has deployed tariff wars. Despite more than doubling tariff revenues in a year through sweeping levies, the interest on US government debt has surpassed $1 trillion for the first time ever—a consequence of rising public debt and higher interest rates.

Financial repression refers to government intervention in financial markets to suppress and distort market mechanisms. It involves redirecting capital—otherwise destined for more productive uses—toward government objectives through policy tools. Recently, it has become a means to reduce the government’s debt burden, typically by keeping nominal interest rates artificially low or driving real interest rates into negative territory.

The US Federal Reserve is already preparing for yield curve control (YCC) under the pretext of stabilizing long-term rates. YCC is a policy in which the central bank sets a cap on yields for certain maturities of government bonds and pledges to buy unlimited amounts to enforce that ceiling. Unlike quantitative easing (QE), which pre-sets the amount of bond purchases, YCC commits to unlimited buying to maintain the target rate. The Trump administration has floated the idea of not only influencing Fed rate decisions but also forcing the adoption of unconventional tools like YCC. From 1942 to 1951, the US government capped long-term Treasury yields at 2.5% to finance World War II, with the Fed fixing short-term rates through unlimited bond purchases. Recent pressure from Trump on the Fed is seen by some as a modern replay of 1940s-style financial repression. The Bank of Japan has also implemented YCC in the past.

Stablecoin-driven demand for US Treasuries is another factor Trump is counting on. In a potential second Trump administration, it may not be long before the central bank is mobilized to plug fiscal deficits.

Governments could also raise taxes, but higher taxes risk losing votes, as does cutting spending. In Japan, the Ishiba administration, France’s Prime Minister Bayrou, and the UK’s Conservative Party all lost power after opting to raise taxes and cut welfare to reduce interest payments.

Ultimately, the only viable path is to force interest rates below inflation. Political forces advocating this approach are gaining ground, such as Japan’s Sanae Takaichi and France’s far-right National Rally.

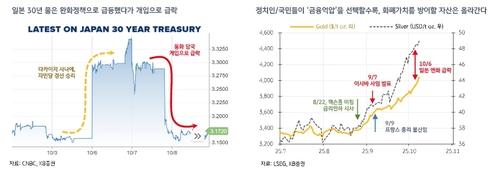

As governments scramble to fill fiscal gaps after four decades of loose spending, investors are moving swiftly. History suggests that only real assets preserve wealth during periods of financial repression, and gold prices are hitting record highs. Silver and Bitcoin, often dubbed “digital gold,” are also rallying. While Washington expects investors to keep buying Treasuries, major Wall Street players are shifting into gold, silver, and Bitcoin.

Meanwhile, expectations of Fed rate cuts and the AI-driven semiconductor cycle among big tech firms are fueling a rally in equities and other risk assets. This “everything rally”—where both risk and safe assets rise—cannot be separated from the effects of financial repression.

*

“After Takaichi, a supporter of Abenomics, won the election, the yen plunged. While inflation was near zero during Abe’s tenure, it now hovers above 3%, causing long-term yields to spike. Japanese authorities responded by intervening to suppress long-term rates. Whether short- or long-term, any spike in yields increases the government’s interest burden, necessitating tools to suppress both. This is a textbook case of financial repression. But there are side effects—namely, currency depreciation. With rates kept far below inflation, few will want to hold the currency. As a result, large sums flow into equities, real estate, and precious metals to hedge against currency weakness, producing the ‘weak yen + asset price boom’ combination.

Is the debt and interest rate problem unique to Japan? Not at all. Japan’s current situation is merely a preview of what the world will face in the future,” said Lee Eun-taek, analyst at KB Securities.

Financial repression is not a government conspiracy, but rather an unavoidable choice in the face of surging interest costs. Citizens, too, resist tax hikes and welfare cuts, often supporting extreme political forces—effectively choosing financial repression themselves.

Perhaps financial repression is not about money, but about direction. Some see shifts in order and new structures emerging within this environment. Even in an era of repression, opportunities are always in motion. Now is the time to look beyond the “visible numbers” and focus on the “hidden direction.” (Securities Editor)

sykwak@yna.co.kr

(End)

© Yonhap Infomax. All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction, redistribution, or AI training/use prohibited.

Copyright © Yonhap Infomax Unauthorized reproduction and redistribution prohibited.